There are starving artists and then there are artists with money. People prefer stories about starving artists who sacrifice material comfort for aesthetic purity. But artists with inheritances may be more common. One of those artists with money was Edith Wharton, and today’s post is all about Edith Wharton for three reasons. I love her books (see, e.g., the shamelessly stolen title), I’ve been watching the new season of the Buccaneers, and I just visited her house in Lenox, Massachusetts, The Mount.

Edith Wharton, then and now, is known for three things: her socially incisive writing, her bad marriage, and her inherited money. Let’s talk about the money. During her lifetime, Wharton received three major inheritances. The first came when her father died in 1882 and she started receiving annual trust distributions worth about $300k in today’s dollars. The second and largest came in 1888, when her cousin Joshua Jones, a major shareholder in the Chemical Bank, left her an inheritance of about $4 million (in today’s dollars). The third came when her mother died in 1901, leaving her enough to fund the construction of The Mount, a project that cost would have cost almost $7 million (in today’s dollars).

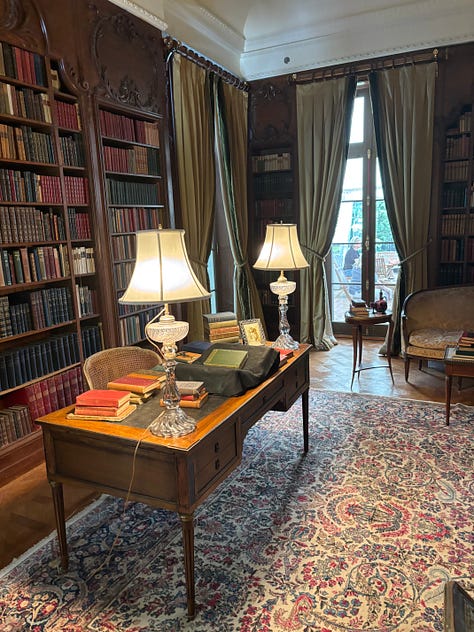

All this inherited money freed Wharton, to some degree, from “society’s expectations” while it also gave her the financial independence to write. Her time at The Mount was a “crucial, creative period,” that was possible thanks to the money she had inherited. She wrote many short stories and magazine articles as well as some of her most famous works including The House of Mirth (1905) and Ethan Frome (1911). By the time she sold The Mount in 1911, Wharton was making over a million dollars a year (in today’s dollars) through the sale of her books and other writings.

Wharton may have been one of the wealthiest writers of her time, but she was not alone in using inherited money to further her writing. Henry James came from a family with generational wealth. Herman Melville relied on an inheritance to fund the writing of Billy Budd. Stephen Crane inherited money from his mother that he used to self-publish his first novel, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, in 1893.

Access to money was equally if not more important for women, as Edith Wharton demonstrated. Money, for women writers and artists, gave them the luxuries of time and sometimes even training. It also, however, allowed them to negotiate their roles within and outside of marriage, as spouses and as caretakers. Take for example two of the most famous female impressionists. Mary Cassatt came from an elite family of bankers and stockbrokers; Berthe Morisot came from a wealthy family that not only supported her artistic passion but also provided her with the resources to pursue education. The list goes on, including notables across the pond like Vita Sackville-West, who fought vigorously to inherit the family estate, and Virginia Woolf, who famously credited her writing success to inheriting £500 a year and having a room of her own.

Looking into this phenomenon of artists who inherit, an economist at the University of Southern Denmark found in a 2019 study that someone whose family has an income of $100,000 is twice as likely to become an artist as a person with a family income of $50,000. Raised in a family with an annual income of $1 million, you are ten times more likely than someone raised in a family with an income of $100,000 to be an artist. It turns out, then, that “family wealth is a connecting thread” even (or especially) in worlds where we like to ignore it.

Loving the substack, Prof. Tait!